Article: Jetteke Bolten-Rempt

|

Jacqueline Ravelli, new dimensions in recent work

Orientation From within the black box intimate salmon pink glows seductively – it has even been described as erotic. The open cube extends diagonally from the wall, so that a surprisingly complex form takes shape. The diagonal, on which the friendship between Piet Mondriaan and Theo van Doesburg foundered in the 1920s, is used by Jacqueline Ravelli in a purely sculptural way: cut off unexpectedly by the wall, the simple object’s third dimension is maximalized and palpable.

Moreover, she gives the object pictorial qualities by painting it – with the traditional material of oil paint – in strongly contrasting colours. From the outside the cube is black and, depending on how the light falls, casts a shadow both outside and inside itself. The black-framed inner space contains five surfaces, two horizontal and five-sided, above and below, and three vertical rectangles, Each of them, partly through the effect of reflection, displays a different intensity of the salmon pink. Daylight, which itself constantly changes with the position of the sun and with weather conditions, is made visible in countless gradations as it is reflected from the salmon-pink surfaces. The static object reveals constant subtle movement. The matt pink that one involuntarily associates with soft material contrasts with the glossy black by which it is sturdily framed, and which, also depending on the light that falls on it, varies from a deep velvety black to charcoal grey, or even lighter shades when it reflects the white wall to which the object is fixed. The work is perfectly crafted so that the eye is nowhere distracted by imperfections. This small masterpiece that Jacqueline Ravelli made in 1985 is emblematic of all her work, in which in a literally many-sided way she combines three-dimensional geometric forms with painting, often in soft pastel colours. The ‘hard’ form and the sensuous colours catch the light that is made intriguingly visible by the abstract, spatial forms.

Narrative elements introduced While Ravelli’s work was originally above all abstract and geometrical, narrative elements make their appearance in her recent work. Not only does she give light a more theatrical role, but topographical elements also provide a certain recognizable element, albeit in the service of her sculptural purpose. She introduces into her vocabulary existing architectural forms, provided by the media or by direct experience, and takes them as a starting point. Their largely fleeting context of light and shade – from which every object we observe receives its form – or mirroring and perspective, is in the new sculptures given a tangible form and presence. A Tibetan house, which she photographed from the screen, is a good example of her mode of procedure.

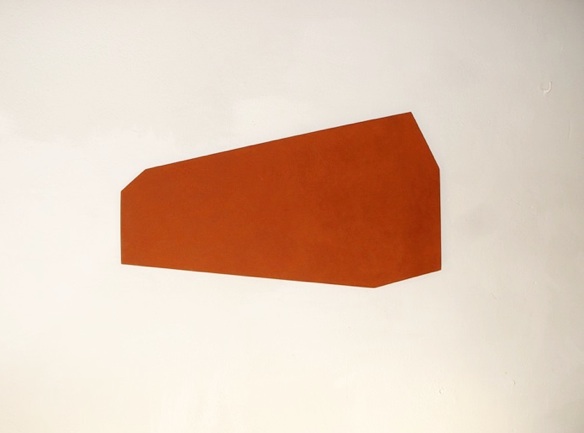

In Tibet Red the house is the starting point, stripped of all details and reduced to its central form, developed three-dimensionally with entrance (but no stairs), ‘window openings’ and an interior space. With its flat rear side against the wall, the sculpture is strictly speaking still a relief, but at the same time verges on an object.

Ravelli has stretched the basic form of the house in Tibet Red so that it becomes a three-dimensional parallelogram. She develops this stereometric form into a monolithic ‘pedestal’ that gives the house a monumental and even sacral quality, which is further reinforced by the monochrome brick-red colour. The meticulous, flawless application of the paint makes the question as to what material has been used irrelevant, just as it is with Japanese lacquer. The structure stands on a sheet of glass which through its transparency functions also as a water surface below which the spatial division of the little building is as it were reflected in broad outline. Besides the contrast between image and reflection she introduces here, with great constructive imagination, the contrast outside/inside. In this work too the real light that is present plays an important part in providing the dark shadows in the small temple, and also the shadows on the wall. Simplicity and complexity go hand in hand, sustained by the precision of the concept and the perfection of its execution. The severe form changes according to the position of the sun (or any other source of light). Key notions in this work are ‘reversal’ and ‘mirroring’, two words for a single idea, although reversal denotes the material aspect of the doubling and mirroring above all the visual aspect. The material realization of these concepts, which spring from Ravelli’s fascination with the appearance of things, generates an entirely new definition of the problem: to bring construction and story into balance in order to give shape to wonderment at a phenomenon. The fascination of the phenomenon of reflection is beautifully embodied in the story of Narcissus told by the Latin poet Ovid in his Metamorphoses (book III, 339-510). The beautiful youth Narcissus, whom everyone falls in love with, is so fascinated by his own reflection that he has no eyes for anything else. ‘He did not know what he was looking at, but was fired by the sight, and excited by the very illusion that deceived his eyes. Poor foolish boy, why vainly grasp at the fleeting image that eludes you? The thing you are seeing does not exist: only turn aside and you will lose what you love. What you see is but the shadow cast by your reflection; in itself it is nothing. It comes with you, and lasts while you are there; it will go when you go, if go you can.[1] Consumed with love for his ungraspable mirror-image, Narcissus pines away. ‘The pyre, the tossing torches, and the bier, were now being prepared, but his body was nowhere to be found. Instead of his corpse, they discovered a flower with a circle of white petals round a yellow centre.[2] A striking aspect of this story is the introduction of the auditory equivalent of mirroring, echo, the reflection of sound. This equally intriguing natural phenomenon is also anthropomorphized by Ovid in the person of the garrulous nymph Echo, punished by the goddess Juno with a ‘repetition defect’. She falls in love with Narcissus: ‘How often she wished to make flattering overtures to him, to approach him with tender pleas! But her handicap prevented this, and would not allow her to speak first; she was ready to do what it would allow, to wait for sounds which she might re-echo with her own voice.[3] Their love is doomed to fail since both exist essentially by virtue of reflection. Jacqueline Ravelli expresses her fascination not through poetic language but by translating the phenomenon ‘reflection’, ‘mirroring’ and ‘shadow’ into construction and colour. Colour covers over the craftsmanship of the construction – image and its double – and makes it into a unity.

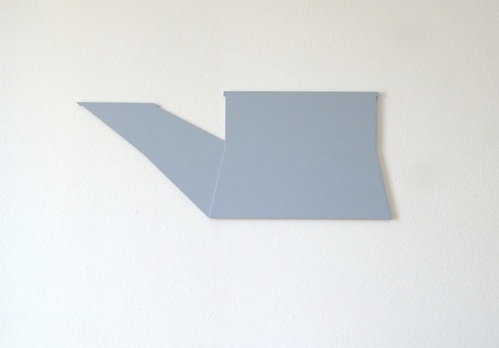

In the low relief built up from two layers Tibet grey Jacqueline Ravelli again takes the main form from the Tibetan house. Here she abstracts the form to an absolute minimum: a flat ‘monolith’. She gives material form to the imaginary cast shadow in sharp perspective – as if one were looking down at the house from a great height – and reworks the whole into the intriguing form of this relief. Painted monochrome grey as it is, this cool relief throws new light on both observation and reality. With minimal means a maximum effect is achieved, telling a universal story of form and space.

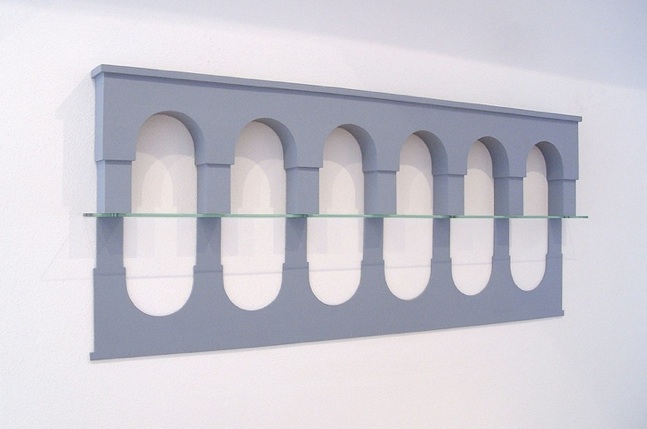

The same principle as Jacqueline Ravelli applied in Tibet Red is applied again in the more recent relief Arcade of 2008-2009.

The six part grey arcade casts its immobile shadow or reflection below the glass surface on which it stands, subtly showing the shift from the upper world to its reflection below. The depth of the relief allows the ‘upper world’ to display a variety of shadow forms, which the flat reflection lacks. Mutatis mutandis, it seems to provide a proof of Plato’s thinking: the reflection is far less finely shaded than reality, just as according to the Greek philosopher everyday sensual reality is but a reflection of the incorruptible, perfect idea that exists beyond time and space. Ravelli presents both the ‘ideal’ arcade and its reflection below the glass surface in abstract, monochrome grey. The many sided game of form and ‘counter-form’, volume and emptiness, light and shade is played by Jacqueline Ravelli according to rules she herself has drawn up, which betray her origins in European minimalism. In this relief she combines her Dutch abstract-geometrical inheritance with the classical tradition she encounters as something self-evident in Italy where she has frequently stayed since 1990. An interesting comparison is provided by the relief Arcade, conceived in 1986 but executed more recently, in 2009.

This relief lacks a narrative element outside itself, while geometrical severity is here further accentuated by rectangularity. The piece gets its charm not only from the enchanting warm yellow but also from the repetitive rhythm of the right-angled ‘gateways’, but it is more abstract and makes far less reference to an observed reality than does the grey Arcade. The monochrome yellow, enlivened by the many shades of light and dark, puts the severity of the form into perspective.

Minimalism As has already been mentioned, Jacqueline Ravelli has her artistic roots in the European minimalism that in the 1960s and ‘70s reacted against the by then hackneyed exuberance of the post-Cobra school and the Abstract Expressionism of the École de Paris and its followers. Simplicity of materials and form (which was often geometrical) was the watchword; in other words ‘less is more’. Ravelli in her turn provided minimalism with a narrative element through associations with (daily) reality. Her sense of humour allows her to modify the deadly seriousness that so often clings to Minimal Art. A nice example is the 8 millimeter-deep relief of a seven-sided figure which bears the title 4 small houses and dates from 1986 – 2008. The form is coloured with brick dust and monochrome red acrylic paint.

While the grey Arcade of 2008-2009 is unmistakably of Italian origin, this seven-sided form is the result, or rather the outline, of a typical Dutch block of ‘single-family dwellings’. Jacqueline Ravelli transforms this everyday subject, which does not exactly fire the imagination, into an intriguing image by reproducing the houses without details, in steep perspective and – albeit flat – as a monolith. The result is a ‘whole’ form or Gestalt, to use the German term. The piece would not be out of place in the context of the exhibition ‘Forms of colour’ (Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, 1966-1967), on which it provides a comment. Ravelli lets the story of reality – the single-family dwellings – come through more strongly without losing the main form. The work plays with perception, echoing the psychology of perception that emerged in the 1930s: our visual perception is not the sum of separate sensations but is determined by the total configuration, the Gestalt. We first see the large form and only after that the details. The brain in this way turns two-dimensional pictures into three-dimensional images. Ravelli’s visual echo seems to reverse this principle: she provides a two-dimensional Gestalt of the original three-dimensional reality. She has reduced the form to its essence in such a way that we ourselves, using the principles of perspective and the recognition of images, project three-dimensionality into it. The matt brick red is literally but also figuratively well chosen, since it refers to the material of which the houses are built and by association gives the sculpture an architectural quality.

Carrying shadow This architectural quality is a feature of all her work, and is certainly to be found in the elegant and at the same time robust sculpture Carrying shadow/Material shadow, dating from 2009. The piece presents a new variation on the archetypal small building she took as her starting point in Tibet red and Tibet grey.

In this piece the base of the building with the cast shadow is turned over, with the freedom that belongs only to creativity, and materialized into a pedestal, which as carrying shadow is integrated into the sculpture itself. Ravelli provides here a new solution for the ancient sculptural problem of the plinth. The main form of the building with its inner space, the right-angled block, stands on the three-dimensional trapezium. This time the form does not protrude from the wall but stand free in space. Now there is no reflection but a doubling of it, the two slightly separated. This doubling means that the whole is subtly cut in two in its length, which makes shadows visible, also in the open interior space. The contour of the little building’s shadow is then with trapezium and all erected into a mass of more than a meter high. For the surface of the whole mass she used two sorts of wood veneer, walnut and the much lighter maple. By this choice of material the sculpture becomes an intriguingly constructed natural phenomenon, with no other functional properties than to provide visual challenge.

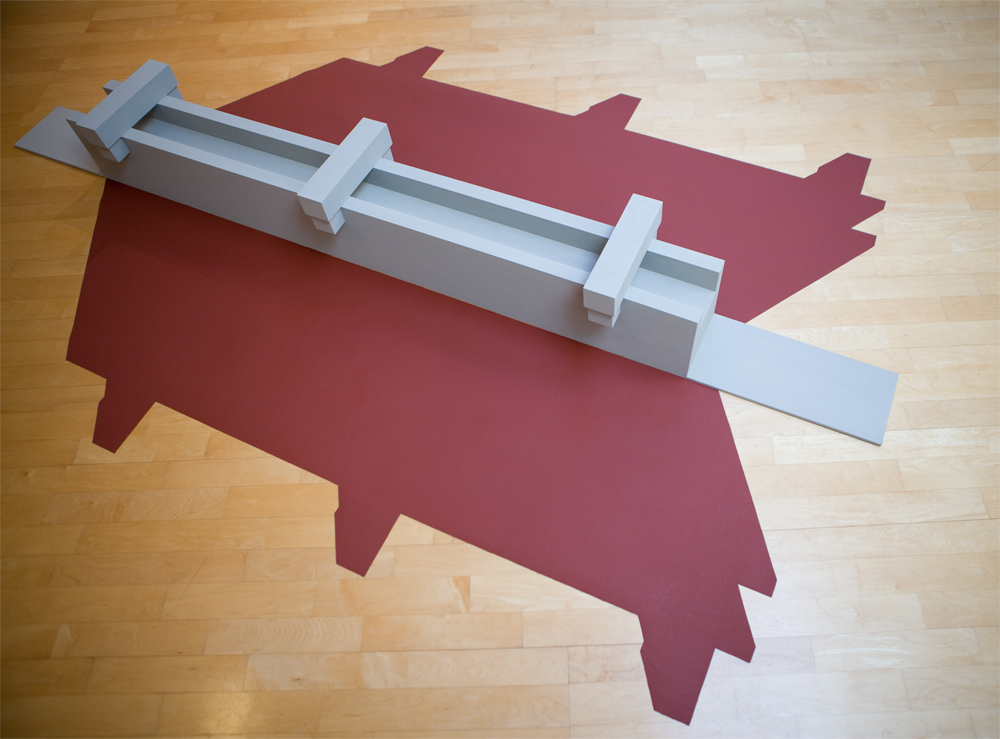

In Wall (2009) Jacqueline Ravelli has succeeded in exploiting all the spatial qualities of her starting point doubling, mirroring or shadowing. The long, grey-painted piece of wall that lies on the ground, spatially detached, consists after a flat ‘run up’ partly of standing sides separated by a gutter and held together by three u-shaped ‘bridge elements’. The part of the wall that is vertical can also be described as a doubling of the sides, which the three horizontal elements not only hold together but also divide rhythmically. The wall then also has a short flat continuation on the ground. The word ‘doubling’ is applicable here above all since on either side of the wall its cast shadow is applied to the floor as a flat shape in lighter grey. This doubling comes about since the artist has taken the freedom to establish the low, imaginary light source that shines on the wall from a great distance and then to turn around 180 degrees and repeat the process. The reference to a possibly observed phenomenon is by this surreal doubling abstracted to a many-sided, partly virtual volume that is related with minimal means to the floor surface and the space above it.

About Jacqueline Ravelli The artist/sculptor Jacqueline Ravelli, born and bred in the Netherlands, comes from the modernist tradition that in the form of Minimal Art played an important part in her native country during the 1960s and ‘70s. She is able to use the more or less objective visual vocabulary of abstract geometry to create original and entirely personal works through subtle spatial constructions, surprising transections and sensual use of colour. In her recent work she adds a narrative element by giving an explicit and theatrical role to light and its opposite, shadow, and also to the related phenomenon of mirroring. In this she is on the one hand influenced by the relaxation of ‘the rules of minimal art’ associated with postmodernist aversion to dogmatism. On the other hand, her partial residence in Italy has been influential, bringing her in contact with the classical tradition that is found everywhere in Italy and taken for granted, and with light conditions that are much brighter and less diffuse than those of the Netherlands. The photograph here reproduced which she took in Brescia reveals something of what inspires her.

A colonnade in Brescia, photograph Jacqueline Ravelli

Unity of opposites The objects and reliefs of Jacqueline Ravelli balance on the border between sculpture and painting, since they make visible her spatial intuition and fascination while at the same time offering perspectival suggestions through mirroring and doubling. Moreover, she introduces a balance between the construction of the piece and its story. Through the monochrome colours she applies and through the gradations produced by natural light, she allows the form, fixed and geometrical though it is, to ‘dematerialize’. It is this unity of assumed opposites that gives her recent work surprising, new dimensions.

Jetteke Bolten-Rempt, 2011 Former director Leiden city museum de Lakenhal.

1 Ovid, Metamorphoses, translated by Mary Innes, Penguin 1955 p. 85 2 ibid. p. 87 3 ibid, p. 84 |

Arcade 2008-2009 oil on plywood glass 127.5 x 53.5 x 6.5 cm

Arcade 2008-2009 oil on plywood glass 127.5 x 53.5 x 6.5 cm